Empowering Youth in the Digital Age: Needs and Challenges for Organizations in Cultivating Digital Citizenship

IN 2021

%

of young people in the EU made daily use of the internet, compared with 80 % for the whole population

%

of young Europeans reported having at least basic digital skills.

%

of young people wrote code in a programming language.

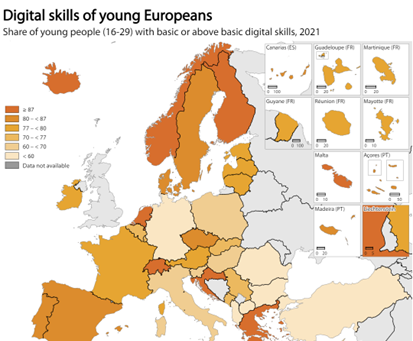

The research “Being young in Europe today – Digital World” , provides more data about young people and how digitally savvy they are and what are the digital gaps that exist in Europe today. For example, the research shows that in 2021, 95 % of young people aged 16-29 years in the EU reported using the internet every day compared to 80 % of the whole adult population. In 21 EU Member States, the share was at least 95 %. The lowest shares of daily internet use among young people were recorded in Bulgaria and France at 91 %.

Important aspect for digital citizenship is fact checking and this research shows that despite the high number of young people using the internet, only 36%, at EU level, engage in activities related to fact-checking online information and its sources. Only in five countries, is the share of young people who assess the truthfulness of the internet content above 50 % (the Netherlands, Ireland, Luxembourg, Finland and Sweden). The lowest shares are recorded in Bulgaria (24 %), Lithuania (22 %), Romania (21 %) and Cyprus (18 %). The share of young people fact-checking their internet sources is higher than the EU average in Norway and Iceland.

Interaction with public authorities and thus participating more actively in the public life is part of the digital citizenship and these data show that while for participating in social networks and writing code young people seem to be at a considerable advantage compared to the adult population as a whole, in other activities such as interacting with public authorities and seeking health information online, the corresponding gap was much narrower. Young people aged 16 to 29 years were, on average, more likely to interact online with public authorities than the total population.

Six EU countries recorded at least 90 % of the young population using the internet for interacting with public authorities. These were (in increasing order of percentage) Latvia, Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Estonia, and Finland. By contrast, the lowest shares were observed in Italy, Bulgaria and Romania. However, in four countries (Romania, France, Italy, and Luxembourg) there is a higher percentage of adults using the internet when interacting with public authorities than young people.

As regards EFTA countries, more than 80 % of adults and young people used the internet for interacting with public authorities in 2021, which was well above the EU average. Among the candidate countries, Turkey had the largest share of both adults and young people interacting with public authorities via the internet at 59 % and 76 %, respectively. All other candidate countries were below the EU average.

Some key issues and debates are ongoing in Europe regarding the needs and challenges of digital citizenship. Many of these topics are part of much bigger debates that affect all parts of society, not just young people. They reflect the rapid changes that are happening in society because of digitalization and the effect this is having on democracy. That is where digital citizenship education comes in. There are many questions that still need to be clarified and debated further:

• How can we ensure digital citizenship education tools are accessible and inclusive to a wide range of young people? Is the transformation into a digital citizenship possible for everybody or does the digital divide still exist? Digital citizenship has not reached a global expansion.

• The digital divide still exists for at least two reasons. It raises the question whether or not access to the internet and social media is a human right. There are the issues of governmental control and censorship, which prohibits citizens from using the digital platforms for political purposes.

• Who should be providing education? Should the schools take over these tasks, or civil society organisations?

• What competencies do youth organizations and young people need?

• How do we connect online discussion and debate to policy making and be really heard?

• How do we deal with issues that affect young people’s media consumption such as fake news and information disorder?

• How do we promote young people’s digital safety and data privacy? Privacy and security is an important domain in digital citizenship education that has to be tended to by governments, educational authorities, families and young people themselves. Should blockchain technology be added to the learning agenda, as it holds great promise for solving many of the dilemmas and challenges such as privacy, data protection, digital identity management and cyber security?

• How can we ensure that the internet is governed in a way that supports democracy, human rights, and the rule of law?